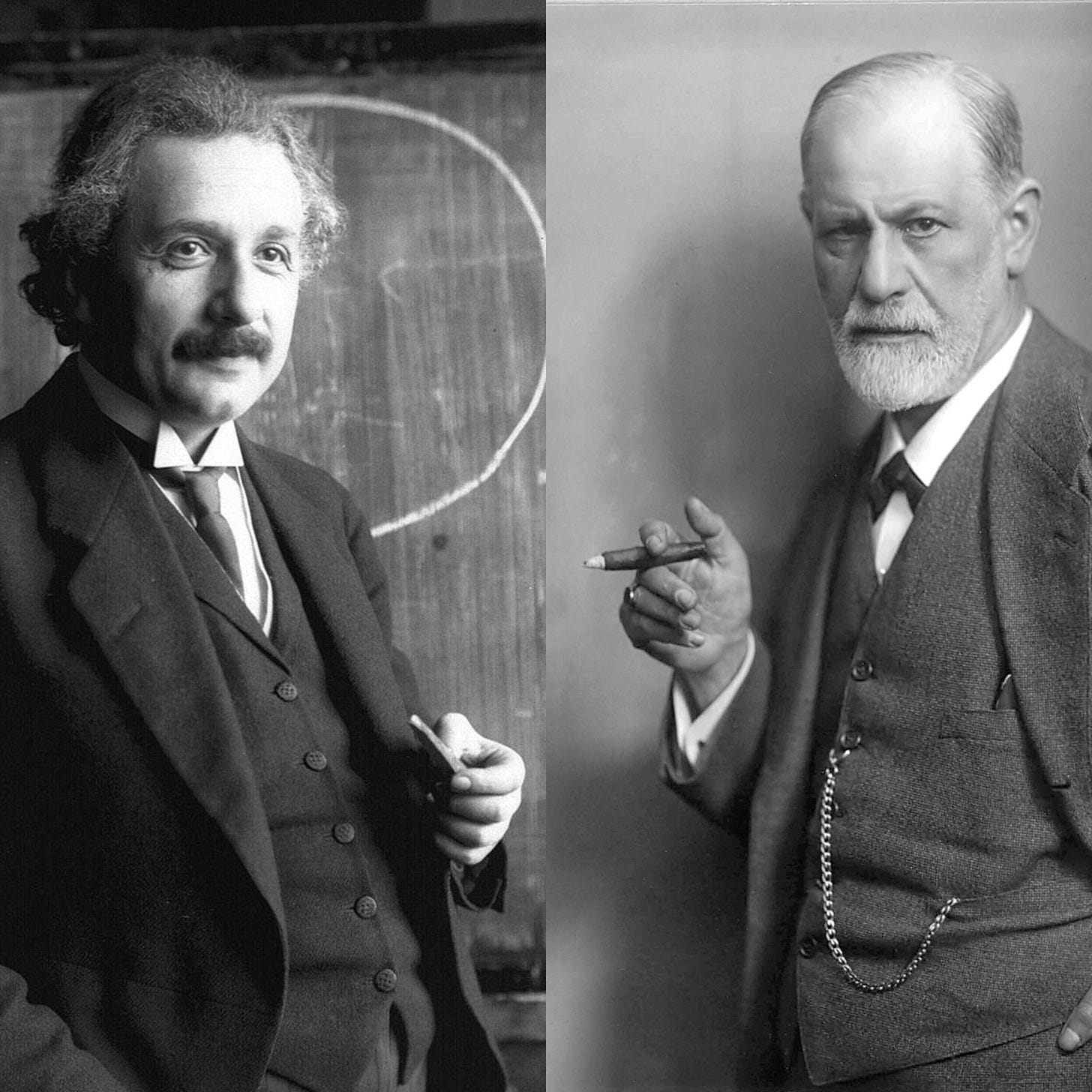

Freud and Einstein on war

With conflict upon us, what can we learn from their little-known exchange of ideas

Hey, Mr. Freud – Mr. Psychology Man – do you have any thoughts on how to stop humans from getting into wars?

This was the essence of the question that famed physicist Albert Einstein posed to Sigmund Freud on July 30, 1932, exactly six months before Adolf Hitler became Germany's new chancellor. Good timing.

Einstein was still a professor at the University of Berlin (he was about to leave Germany for good) while Freud continued his psychoanalytic practice and writing in Vienna.

Einstein had asked Freud the question in an open letter. Freud would respond in kind a few months later. I learned about the correspondence while poking around online and was surprised to discover that the exchange (titled Why War?) had received little attention. Really? As Europe was about to explode in war, again?

You can read the exchange as well as the views of others who commented on it in Einstein on Peace.

What can we learn from Einstein and Freud as conflict rears its ugly head in our own time?

Before we get to that, here’s a bit of background along with a summary of the exchange:

Einstein’s letter to Freud was homework of sorts. The League of Nations, founded to maintain global peace in the aftermath of World War I, asked Einstein to pick a problem of his choosing and an interlocutor. The physicist would then initiate “a frank exchange of views.” Einstein chose another towering intellect of the time, Freud.

“This is the problem,” Einstein starts off. “Is there any way of delivering mankind from the menace of war? It is common knowledge that, with the advance of modern science, this issue has come to mean a matter of life and death for Civilization as we know it.”

Nobody has been able to solve this problem, Einstein adds, admitting that he too is stumped. His own field of expertise – physics – “affords no insight into the dark places of human will and feeling.” What he needs is someone with “far-reaching knowledge of man’s instinctive life” (ahem… Freud).

Einstein then offers what he calls a “superficial” solution to the problem: “the setting up, by international consent, of a legislative and judicial body to settle every conflict arising between nations.”

Nice idea, but it would take another world war before the United Nations came into being in 1945. The only existing body at the time was the League of Nations, which, as both Freud and Einstein allude to, was too weak to deal with mounting tensions between nations. (Side note: Einstein makes no mention of it when offering this suggestion. A veiled critique?)

The problem, Einstein continues, is that such a body would still be “a human institution” with all the “strong psychological factors” at play. What do you do about power hungry nations or groups within nations that advance their own interests at the expense of everyone else? All it takes is a “small clique to bend the will of the majority…rousing men to such wild enthusiasm, even to sacrifice their lives.”

“Man has within him a lust for hatred and destruction,” Einstein adds. How can we “proof” man “against the psychosis of hate and destructiveness?”

The question took Freud by surprise. The two men, both Jews, had previously exchanged friendly messages on special occasions like birthdays. They met in person once at a Christmas gathering in 1926. But on this occasion Einstein put Freud on the spot professionally, asking him blunt questions about a problem that went to the heart of Freud’s theories.

In his reply, Freud writes that he was “dumbfounded” at first because the problem Einstein raised seemed to be a “matter of practical politics.” He soon realized that Einstein wasn’t asking him about that. He wanted Freud to tackle the issue as a psychologist.

“Conflicts of interest between man and man are resolved, in principle, by the recourse to violence,” Freud starts off. “It is the same in the animal kingdom, from which man cannot claim exclusion.”

“The most casual glance at world history will show an unending series of conflicts,” he adds. “You surmise that man has in him an active instinct for hatred and destruction… I entirely agree with you.”

This doesn’t mean that such an instinct is bad, Freud explains, for instincts are of two kinds: erotic and destructive. Erotic instincts seek to “conserve and unify” while destructive ones, well, they speak for themselves, to “destroy and kill.” The two – love and hate – are in all of us and almost always merge to differing degrees.

Freud gives the example of someone, a soldier perhaps, who is desperate to save himself in a conflict. “Self-preservation is certainly of an erotic nature, but to gain its end this very instinct necessitates aggressive action,” he writes. In other words, if a soldier is hellbent on saving himself, he must be prepared to kill. Love and destruction go hand in hand.

And here is where Freud offers a psychological solution to war: “If the propensity for war is due to the destructive instinct, we always have its counter-agent, Eros, at hand. All that produces ties of sentiment between man and man must serve us as war's antidote.”

The idea raises more questions than it answers. How do we strengthen ties of sentiment between man and man? And if the destructive instinct can never be eradicated, only suppressed, what hope is there of humanity ever evolving beyond war?

Freud’s hope is on the “cultural development of mankind” or as he also calls it, the “organic process” of “civilization.”

“To this processus we owe all that is best in our composition, but also much that makes for human suffering,” he writes.

This is classic Freud. Here’s the basic idea: By developing our “culture” or “civilization” we create social impediments to our actions. We suppress our aggressive instincts for the good of society (Freud adds sexual impulses as well – but that’s certainly a topic for another day). The downside is suffering as individuals are prevented from releasing pent up energy. The benefit is that the growth of culture helps humanity strengthen the intellect, which, as Freud writes, “tends to master our instinctive life.”

Here he is in his own words:

On the psychological side two of the most important phenomena of culture are, firstly, a strengthening of the intellect, which tends to master our instinctive life, and, secondly, an introversion of the aggressive impulse, with all its consequent benefits and perils. Now war runs most emphatically counter to the psychic disposition imposed on us by the growth of culture; we are therefore bound to resent war, to find it utterly intolerable.

Utterly intolerable? Hmm…

In his reply, Einstein is curiously silent on these ideas. He merely praises Freud for a “gratifying gift to the League of Nations” and a “magnificent” letter.

Five months later, Einstein left Germany for good. The Nazis were ascendant, antisemitism rampant, and an aura of fear pushed some Jews to emigrate. By the time the correspondence was published in 1933 Hitler was already in power in Germany. When the Nazis took over Vienna in 1938 Freud had risked everything in staying as long as he had. With the help of powerful friends, he escaped and settled in London.

War again is upon us – in the Middle East and Ukraine. Is there anything we can learn from Einstein and Freud?

Do we have a destructive instinct? Honestly, who the hell knows? It does seem that humans have a unique ability to kill each other unlike any creature in the animal world. One study claims that “humans are six times more likely to kill each other than the average mammal.” Whether it’s instinctual or not, I think it’s safe to assume we’re pretty violent.

Here’s another question: Are we born with a violent disposition or do we get it from our social environment? Scholars have gone both ways on that.

What’s curious to me about this exchange is that although Einstein and Freud agree that violence is instinctual to man, they don’t make a big distinction between violence and warfare. The two are not the same. Warfare is a collective endeavor that requires organization and often a justification. How else do you motivate so many people to risk their necks for a cause?

So warfare cannot be merely instinctual. Or can it?

It is hard to believe that Russia would start a major-league war on European soil after the massive death and destruction of two world wars. But we are where we are. The Kremlin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine has been incredibly brutal.

The fighting in the Middle East between Israel and Hamas (along with Iranian proxy groups) has been a regular occurrence, although this round of fighting has reached a new level of intensity.

“You are amazed that it is so easy to infect men with the war fever,” Freud tells Einstein. Freud shared that sentiment.

This is all getting pretty depressing. Let me fish for some positives to end on…

First, Freud’s idea of “eros” (the desire to conserve and unify as a counter to human destructiveness) could be fruitful to explore on an international level. How do we more effectively strengthen “ties of sentiment between man and man” across boundaries, across nations?

Second, we now have a host of global institutions with more authority to tackle the problem of war, the United Nations chief among them. Yet the institution feels static. How can Russia, with its atrocities in Ukraine, have a veto on Security Council resolutions?

The moment is ripe for reform.

In his response to Einstein, Freud writes that the League of Nations was “an experiment the like of which has rarely – never before, perhaps, on such a scale – been attempted in the course of history.”

The same is true of the U.N.

And like the League of Nations, it stands at a crossroads. Let’s hope this experiment evolves for the better.

Notes:

https://bigthink.com/the-present/einstein-freud-letter/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001tr2s

https://www.themarginalian.org/2013/05/06/why-war-einstein-freud/

https://www.public.asu.edu/~jmlynch/273/documents/FreudEinstein.pdf

https://en.unesco.org/courier/may-1985/why-war-letter-albert-einstein-sigmund-freud

https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Freud_War_and_Death.pdf

Feral Brain participates in the Amazon affiliate program. This means that when you purchase a book with an Amazon link to it, I get a small commission.

Very well written Terry! If you keep writing this way and about these topics you'll find yourself on a one way train ride to a gritty, old yellow brick building with black smoke coming out the chimneys.

Our violent actions come both from our nature and the environment we're raised in. I think it's a mix of the two. Violence and injury can be curbed by empathy with action on a grand scale. Consider the response to the polio academic. Faith can also tap down hate. But faith can easily be manipulated by religion both by the nature of people and the environment.

I'm tired of all this conflict and hate going around. The U.N.- forget about it. If a person can just try to do one nice thing for another each day we'd have a lot more peace. This doesn't show intellectual growth, it shows doing the right thing and where it comes from is irrelevant. However, good acts bring joy. Joy is different than pleasure. Christmas shouldn't be a big f***ing deal, it should be everyday. People don't even want to say Christmas but they'll effortlessly say the word above with the stars.

Look, when I was a young man I had all the answers. After law school I had all the questions. Now at 64 I'm just confused. I doubt intellectuals like Freud and Einstein can figure this out any more than you or I can. Certainly, all the "smart" people we allegedly have often cause a lot of damage to others.

I very much enjoyed this. I did not know about the correspondence.

Freud understands violence and self-interest as intrinsic to human nature. Madison had already taught us to create a government that takes human nature into account. That is not easy, but it is part of the solution.

The same holds on the IR level. A problem with the UN is that it doesn’t consider human nature: The General Assembly is a mob - raw democracy driven by base motives, not overarching values.

You mentioned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. From Putin’s viewpoint, he had cause – feeling surrounded by a threatening NATO.

Hamas, in its barbarism, sees itself as justified in trying to exterminate Israel. It explained why in a statement issued on October 7 and its founding charter.

Individuals, nations, and nonstate actors may be violent, self-interested, and dangerous, yet they need alibis and justifications to “civilize” their actions. You made me think. Keep writing.